Although I believe that the Closet Music project is an original one, there are of course various sources of inspiration, and precedents for music written in non-notational modes. Augenmusik, graphic scores and the Fluxus movement are three important fore-runners of Closet Music.

Throughout the history of Western music notation, the presentation of the score as a whole (not just the method of notation) has frequently been of importance. Augenmusik is a wide term indicating a visual element which has no musical instruction but which adds extra meaning for the reader and performer. For example, the beautiful illuminated sacred manuscripts of the middle ages imply the importance of the music, nod to the wealth of the owner and monetary importance of the work, and surely add to the joy and depth of meaning in the reading and contemplation of the work. In secular music, Belle, bonne, sage (below) by Baude Codier (c.1380-c.1440) is a classic example of Augenmusik. Here the visual shape plays no part in the ‘aloud’ performance (though there are red notes which indicate rhythmic variation) – but for the recipient of the manuscript, how much would their performance, and appreciation of the music, be enhanced by such a personal and sensually delightful work?

In the modern age, George Crumb similarly uses shaped music to influence the players’ perception of meaning, though this cannot be heard in a performance – Spiral Galaxy from Makrokosmos volume 1 is a good example, with the staves spiralling in on themselves. Recently, Pat Muchmore defended Augenmusik (in the New York Times, August 3rd 2011), calling music which employs such non-functional elements ‘ergodic’ and discussing the almost sensual joy of playing from scores which have a highly visual element: ‘I love both creating and reading these scores: it’s ever so slightly magical’.

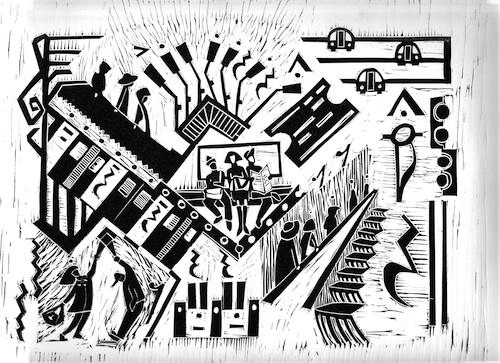

Even closer to the concept of Closet Music is the use of graphic scores: scores which use non-conventional notation such as images, diagrams, lines and colour to guide a performance. These range from highly rules-based works, to those which exist to provide suggestions for improvisation – and some, like Mark Applebaum’s Metaphysics of Notation, are beautiful art works in their own right, however they are used musically. Aria by John Cage and Stripsody by Cathy Berberian are further classic examples - and both could be wonderful specimens of Closet Music had they not been intended for public performance.

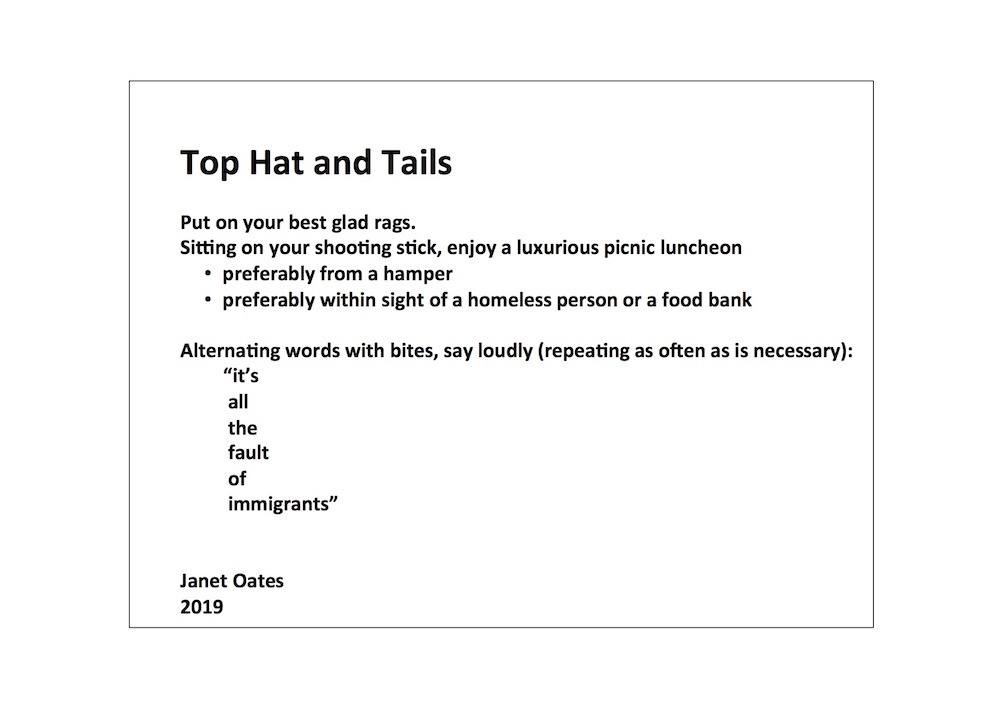

In the 60s, particularly in America, the Fluxus movement expanded the idea of what music is, deliberately blurring the boundaries between music/noise/silence, and composer/performer/audience. Again there is an overlap here with Closet Music: the enjoyment of ‘intermedia’ (the intersection of different media), the frequent use of everyday/found objects/sounds and the idea that anyone can perform this ‘art’ is key to Fluxus and to many of the closet music works. Some of the text-based closet music works resemble event scores (text instructions for events), central to the Fluxus movement – such as those by Alison Knowles, Yoko Ono, Georges Brecht, and others. Event scores are still flourishing today, as evidenced in the wonderful volume Word Events: Perspectives on verbal notation by John Lely and James Saunders (Continuum Books, 2012, NY); the works of Amnon Wolman; some pieces in the gorgeous anthology Writing to be Seen – an anthology of later 20th-century visio-textual art, Runaway Spoon Press 2001); and a recent series of Fluxus-type performance events in Cardiff by the NewCelf group.

The key differences between Fluxus scores (whose influence our composers freely acknowledge) and Closet Music pieces is that Closet Music is a private and essentially sound-based concept, while Fluxes works are have a performative intention and need not have any sound involved.

Event scores are still a valid, ongoing form of art, as is evident from a recent exploration / anthology of texts: a wonderful volume called Word Events: perspectives on verbal notation by John Lely and James Saunders (Continuum Books, 2012, NY), which includes many composers’ discussions of text scores. Almost all of the scores are intended to be ‘performed’ (while this concept is of course open to interpretation), though there are many that are more intimate and internal (such as a few in Grapefruit by Yoko Ono (1964) or Arthur Bull (1994)). One composer who has been producing text scores (since the late 1990s) which are exactly congruent with Closet music is Amnon Wolman: he calls his collection ‘imaginary pieces’ and they can be seen at his website www.ammonwolman.org.